You are a blind man, a disabled person. When you yourself need the help of others, what social work are you going to do?"

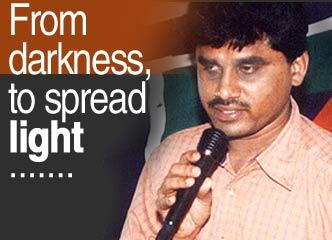

This was the encouragement Murali Padmanabhan, 33, project leader of the Madras unit of Cheshire Homes India, got from a lady working for the Guild of Service when he went to her for a reference letter.

Today, Murali can afford to look back on the incident and laugh. But 10 years ago, such nasty comments devastated him.

What helped him rise above such disillusionments, which were aplenty in the beginning, was his determination to succeed.

Murali was not born blind. When his glasses became thicker and thicker during his schooldays in Trichy, he was brought to the Sankara Netralaya in Chennai. That was when he learnt for the first time that he was suffering from retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative disease of the retina that would ultimately result in blindness.

Murali was just 15 years old when he learnt the truth. To say that he was devastated would be an understatement. "Even with my thick glasses," he recalls, "I used to play cricket for my school as a fast bowler."

By the time he was 20, the power of his corrective lenses had gone up to +20! Still, he continued with his college education.

But soon it became so bad that he found it difficult to read his accountancy books or The Hindu, the newspaper he loved and devoured from the front page to the last every day!

"I had prepared myself for the eventuality," he says. "At night I had already become totally blind by then. But what saddened me was that I couldn't read The Hindu anymore!"

With his fading eyesight faded Murali's dream of becoming an IAS officer or a chartered accountant. But Murali did not give up. "I started looking at an alternative career, a different kind of life where there was no light," he says. "I decided not to sit idle and wallow in self-pity."

His family, an "ordinary, middle-class family", did not own any ancestral property. So Murali knew it was entirely up to him to go up or come down. "I do not know how I was motivated," he adds, "but I decided to go up."

As a first step, he enrolled himself for a course in Braille and stenography at a rehabilitation centre attached to a college. It was no easy task convincing the person in charge. His contention: "You are going to lose sight completely some time later. Why do you want to learn Braille now? Why make a coffin for yourself when you are alive?"

Murali was adamant. Most of those who were learning Braille at the centre were born blind. He on the other hand had been pushed into the world of darkness just a few months ago. But Murali passed the Braille and stenography tests with top honours. Now, he wanted to do 'something worthwhile in life.'

"I went to see the research officer at the rehabilitation centre in Chennai, and it was he who asked me, 'Why don't you do social work'?" Murali liked the suggestion and approached the Guild of Service for a reference letter to apply for a post-graduate course in social work.

That was when the incident with the unhelpful woman occurred. "I had to face a lot of humiliation," Murali remembers. "But I took every insult and every word of humiliation as a stepping stone."

Even before the results of his MSW (Master's in Social Work) examination were out, Murali joined the Bangalore-based Action on Disability and Development India, an organisation founded in the United Kingdom with networks in 18 countries. What made him confident about his abilities were the visits he made all alone to several unknown villages during the training period.

"I was a bit sceptical initially when they asked me to go to a village," he admits. "I asked myself, will I be able to do it? Is it possible? Then I convinced myself, yes, it is possible. The first day, they dropped me at the village and left."

Since then, Murali has been marching along. In the first village itself, he became a role model to a blind college student who had never gone anywhere alone.

"I told the boy not to take anyone's help when travelling to college or anywhere," he says. "That was the first counselling session I did, rather successfully!

"Till then, I had taken counselling from others. Now, there I was, counselling villagers on various issues. Because I was a disabled person and I went to them, villagers listened to me and did whatever I ask them to. Their attitude was, if he can come all the way from a village to help us we should do what he tells us!"

Today, Murali's work includes almost 20 days of travelling a month to various villages. Wherever he goes, the first question he is asked is whether he works in an orchestra. The second: why isn't he doing something that does not involve travelling, like managing a telephone booth?

But Murali is happy that he does not fit into the stereotypical image of a blind person and is doing something different. He has even travelled to The Netherlands all alone to obtain a diploma in development and social justice, a 50 day course sponsored by the Dutch ministry of foreign affairs and co-operation. "There were 20 participants from all over the world," Murali recalls, "and I was the only 'disabled' person in the group! I was not sure whether the group would accept me, but they all turned out to be so helpful!"

Back from the Netherlands with his diploma, Murali felt he was stagnating at the ADDI. So, he decided to join the Cheshire Homes Madras as a project leader, though he was of the opinion that the organisation "knew only charity and welfare and not development or human rights".

What attracted him were the new schemes laid out by the training and development unit of Leonard Cheshire International at Bangalore. They planned to improve the quality of life of the inmates and promote community-based services. Murali took the offer up as a challenge and decided to change Cheshire Homes into an institution for development and rehabilitation by involving the family and community.

The person who opposed him initially, Maureen Murari, in charge of the Chennai unit, later became his strongest supporter. "Without her, we could not possibly have seen the community project through," says Murali. "It was she who brought in the money [about £10,000 by the small grants scheme of the British deputy high commission, Chennai]; it was she who created a team for the project."

For the first time in the history of Cheshire Homes, Thiramai (ability), a community programme, was launched by the Chennai unit. "Within nine months, we have achieved the distinction of being a training ground for other Cheshire Homes! Till now, community programme was an unparliamentary word as far as Cheshire Homes was concerned!" a happy Murali remarks.

Murali believes that charity or welfare will never help a disabled person in the long run. "They will not become independent or a part of society through charity or welfare schemes," he says. "Disabled people are very often ostracised and excluded from societal activities. This has to change. The change will take place only if we empower them.

"I tell them that the disabled people themselves, their family, and the community are responsible for their development. It is in order to ensure that the programme continues even after we leave that we involve the community."

Murali's team chose 15 socially and economically backward and marginalised panchayats in Kancheepuram district for the programme. They found that the disabled constituted 1 percent of the population (or 370 people). After identifying them and assessing their potential professionally, an action plan was drawn up for each of these 370 persons.

"If the family trains them in their day-to-day activities," he says, "they will not end up in institutions like this. Their major problem is taking care of themselves."

To educate the family and the disabled, the rehabilitation workers counselled them daily or weekly, depending on requirement. They also trained volunteers in the village to continue the work. After all, the team's motto is 'from professionals to barefoot workers!'

In the case of children, after taking care of the medical needs of each child, the team explores the possibility of educating it in a normal school to ensure the integration of the disabled in society. "Disabled children also have the right to go to school," Murali explains. "Our argument is that it is not said anywhere that schools were only for the non-disabled."

The first objection in such cases usually comes from the teachers. So, the volunteers educate the teachers and also other children, "who can be extremely cruel to disabled children."

The team also organises community meetings, which mainly include women groups, to educate them about and sensitize them to the disabled. It is only after covering all these bases that the rehabilitation of the disabled can begin.

In less than one year, the team has rehabilitated quite a few disabled villagers by giving them loans to start small businesses. For example, Logu, a physically disabled person who didn't have any work till the team reached his village, now has a shop that sells flowers. Girija, a paraplegic, sells handicrafts from her own shop and earns a decent amount every month. She is much admired and respected in the village for her entrepreneurial spirit.

"We have a long way to go," admits Murali. "Many more villages to cover, many more people to make independent. But I want to tell you something. I love to meet that lady who worked for the Guild of Service and tell her what I am doing now!"

There is a wry smile on his face as he says that.

Photograph: Sreeram Selvaraj | Image: Uttam Ghosh